If you know where to look in the Mississippi Delta, you can find traces of what a culture spent decades trying to eradicate.

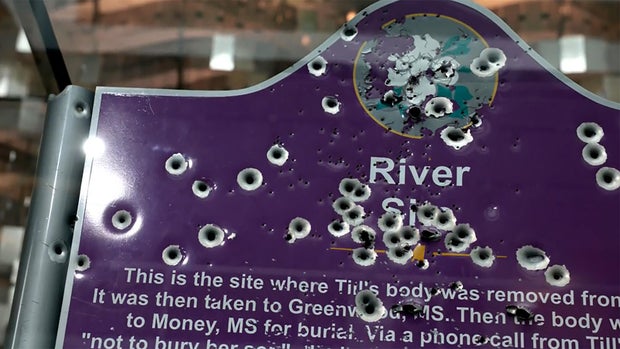

This plaque on the Tallahatchie River – changed periodically whenever it is riddled with bullets – marks the spot where the young The brutally beaten body of Emmett Till was pulled from the water.A cotton fan was wrapped around his neck, secured with barbed wire.

CBS News

The country store where Till whistled at a white woman – the “capital crime” of this 14-year-old boy – will soon disappear entirely, being reclaimed by nature. Author Wright Thompson says the vines growing over it are “a perfect reflection of abolition, and an attempt to pretend it never happened.”

CBS News

But at the same place where this lynching had unfolded nearly 70 years ago – nothing. Every day, people drive by a barn just outside Drew, Mississippi, with no idea what they're doing – a place where the worst things imaginable happen inside. Can be done. And that's the point, Thompson said.

In his new book, “The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” (Published by Random House), Thompson, who is also a fifth-generation Mississippi Delta cotton farmer, investigates what he calls evil hiding in plain sight. He said, “Like almost everyone in Mississippi or even America, I didn't know about barns.” “If I don't know something essential about the place I think I know best in the world, it means there is something deeply, fundamentally wrong.”

random House

Mississippi in the summer of 1955, when Emmett Till visited relatives, was a different world to this Chicago kid. Unfamiliar with Delta's ways, he had no idea what a high price he would pay for blowing the whistle by targeting a woman who worked at the store. “He whistled at sunset on Wednesday and was taken at 2:30 a.m. on Sunday,” Thompson said.

An 18-year-old sharecropper named Willie Reed was walking near a barn when a truck drove by. He hid while the woman's husband and brother-in-law, who had snatched Till from his bed, dragged the boy to the barn. , “And she heard screams, turning into screams, turning into silence,” Thompson said. Reed went home, “and everyone in his life said, 'Don't say anything. You don't say anything.'”

Instead, Reed gathered all his courage and walked into the courtroom to charge two white men, JW Milam and Roy Bryant, with murder.

Asked why he ignored warnings about keeping quiet, Reed's widow, Juliet, said, “I think it was something about Willie that he wanted to get right.”

While the open casket sparked outrage, Till's mother, Mamie, insisted that, without Willie Reed's bravery, no one would ever have been charged. “It was an all-white jury,” Juliet said, “and the jury was laughing.” [Willie] Was testifying.”

Bryant and Milam were acquitted. Reed must flee to Chicago and change his name. Juliet said that until the day she died she was haunted by the screams she heard.

“The people who did the right thing in this case had their lives deeply affected, if not ruined. And the people who did the worst thing got away with it,” Thompson said.

Thompson says that injustice needs a spotlight in the Delta, where the tendency has always been to keep it hidden.

In 1965, Gloria Dickerson integrated schools in Drew, not far from where Till was murdered. Schools made no mention of Till's death when she was growing up, and today, only 117 words – one paragraph – are used to describe Till's murder in a Mississippi history textbook. “In Mississippi, they won't know about what happened to Emmett Till,” Dickerson said. “It's like the past is being erased.”

She combats that erasure through a program, We2TogetherJo teaches the children at Drew the history that her parents made sure she learned as a child. “When we would walk by that barn, my mother would say, 'That's where Emmett Till was murdered,'” Dickerson said.

She says all children should be taught that history: “Every child; blacks need it, and whites need it, too.”

While Tallahatchie County apologized to the Till family in 2007, and a statue was unveiled in 2022, Maun's legacy remains powerful there.

Rev. Willie Williams, who helps run it Emmett Till Interpretive Center (a non-profit dedicated to Till's memory), said he knew nothing about the barn; His first visit there was two years ago, when he was 60 years old. “I was in high school when I found out [was] The store where Emmett whistled at a white woman. And I grew up in the Delta.”

He believes that not talking about what happened at Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market and Barn was an attempt to erase history.

Today, in the barn where Emmitt Till was murdered, you will find one of the most ordinary objects of everyday life: an outboard motor. Wood flowing from the river. Christmas decorations. across.

CBS News

The barn — owned by a guy who let “Sunday Morning” in but didn't want to talk, and who is negotiating to sell it to Rev. Williams' nonprofit organization — is where the contradictions are most stark. It's hard: the ordinary building so many see, hides extraordinary evil that no one knows about. And, says Thompson, author of “Barn,” that's why they've dug so deeply, so that if the erasure continues, no one can say “we didn't know.”

“Not knowing this means we are competing,” he said. “Silence and erasure are different words for the same thing.”

Read an excerpt: “The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” by Wright Thompson.

For more information:

The story is produced by John Caras. Editor: Mike Levin.

See also: