A study published in the American Journal of Primatology has provided new insights into the emergence of bipedalism in human ancestors. Using advanced 3D scanning techniques, researchers analyzed fossil bones to investigate how early hominins moved, focusing on the transition from tree-dwelling locomotion to upright walking. The research was led by Professor Josep M. Potau from the Human Anatomy and Embryology Unit at the University of Barcelona and Neus Ciurana of Gimmernat University School. Collaborators included a team from the University of Valladolid.

Innovative 3D Analysis Techniques

The study Examined muscle insertion sites in the ulna bone, a key part of the elbow joint, to determine locomotion types among extinct and living primates. The findings suggested that species like Australopithecus and Paranthropus combined upright walking with arboreal movements, akin to modern bonobos (Pan paniscus).

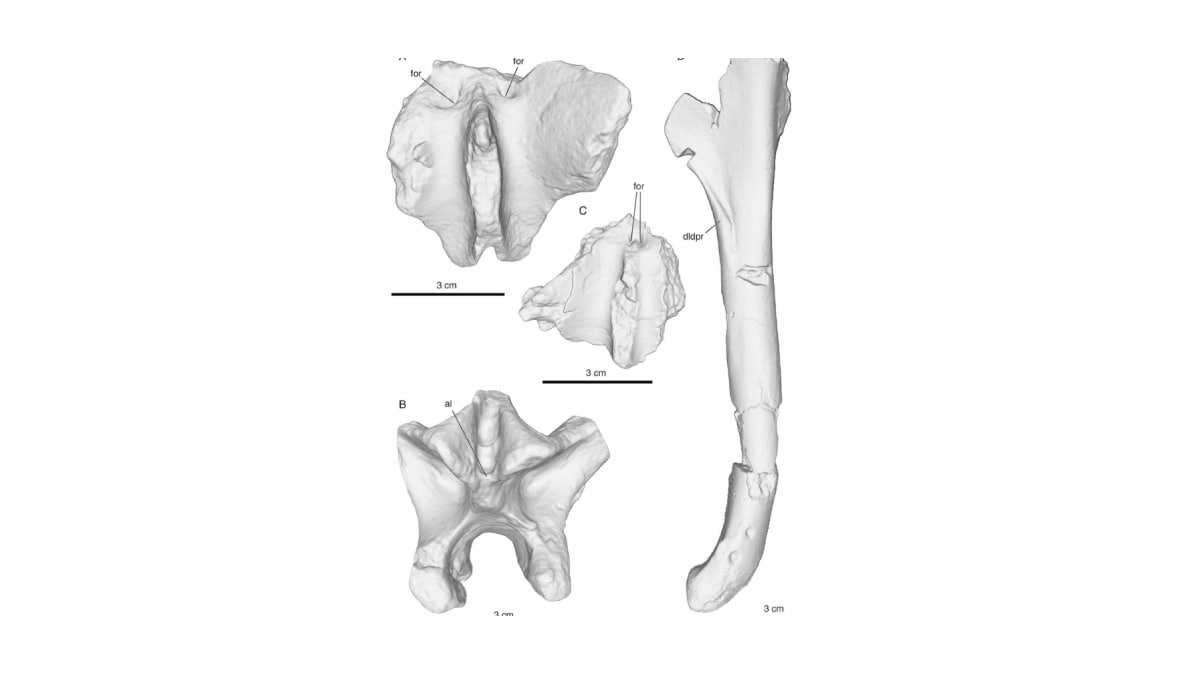

The methodology involved creating detailed 3D models of the ulna from modern primates, humans and fossilized hominins, as per sources. Researchers measured the insertion zones of two crucial muscles: the brachialis, which aids in elbow flexion, and the triceps brachii, responsible for elbow extension.

The study found that arboreal species such as orangutans displayed a larger brachialis insertion area, while terrestrial species like gorillas showed greater development in the triceps brachii region. This comparison helped identify locomotion patterns in extinct species.

In a statement, Potau explained that this muscle ratio allowed researchers to compare extinct species like Australopithecus sediba and Paranthropus boisei to modern bonobos. These fossil species exhibited traits associated with both bipedal and arboreal movements, suggesting they were transitional forms.

Absence of Adaptations for Tree-Dwelling Behaviors

In contrast, fossil species from the Homo genus—such as Homo ergaster, Homo neanderthalensis, and archaic Homo sapiens—displayed muscle insertion proportions similar to modern humans. These findings indicate the absence of adaptations for tree-dwelling behaviors in these species, highlighting their commitment to bipedalism.

The study offers a foundation for future research into the evolution of locomotion. As stated in different publications, similar methods could be applied to other anatomical areas to deeper understanding of human evolutionary history.